- KDE Linux offers an immutable foundation with atomic updates, Wayland, and Flatpak/Snap apps.

- Unlike KDE Neon, it's not just the latest packages, but a technical benchmark with reproducibility and containers.

- GNOME OS is moving in the same direction with carbonOS, systemd-homed, and systemd-sysupdate as key pieces.

- The KDE ecosystem offers Plasma and mature frameworks across multiple distros, for all paces and profiles.

The idea of a "KDE community" system has been around for a while and although has not yet materialized as a stable versionThe concept has made the leap into public conversation. KDE Linux aims to become a general-purpose distribution with a clear identity and the Plasma ecosystem as its main focus, a movement that doesn't aim to replace the existing distribution but rather raises the technical and experience bar for those who choose KDE.

In recent months, some relevant details have been circulating: Arch as the base build tool, an immutable system with atomic updates, decoupled apps, and a strong support for Flatpak (and also Snap), all seasoned with Wayland by default and a commitment to build reproducibility. If you're interested in understanding what exactly KDE Linux offers, how it differs from KDE Neon, and how the parallel GNOME OS effort fits inHere is a complete guide that compiles and reorganizes all the known information.

What is KDE Linux and why is it defined as general purpose?

The community describes it as a reference implementation: KDE Linux would be “the ideal operating system” for developing and using Plasma and KDE applications with consistent guarantees. More than a derivative of Arch, it is an immutable system that uses Arch packages as raw material., so much so that it doesn't even include that distribution's traditional package manager; it's not a typical "Arch-based" package, but rather its own system base with a different approach.

This approach results in atomically updatable system images, with multiple cached versions (up to five) to make it easy to roll back if something goes wrong. With Btrfs and snapshots as a safety net, and Wayland enabled by defaultThe goal is to minimize the risk of system changes and ensure that each update is predictable, fast, and recoverable.

Another pillar is the separation between the system base and applications. Apps come primarily from Flatpak and also Snap, keeping the immutable layer intact. For advanced needs, KDE Linux offers several paths: Use Distrobox or Toolbox (already pre-installed) to bring in classic packages in containers, use Homebrew in your home directory, compile from the base using systemd-sysext, or pull an AppImage. All of these paths help cover specialized software not listed in Discover.

The graphic support is designed to be clear and legally secure. For modern NVIDIA GPUs (Turing/GTX 1630 and higher) open modules and corresponding user space are pre-installed, so that the experience "runs smoothly." Pre-Turing models, on the other hand, require proprietary modules that can't be hot-loaded due to the immutability of the base, and redistributing them pre-installed falls into a legal gray area; that's why they're not included. In those cases, Nouveau can serve as a less efficient alternative, although its activation currently requires manual steps and technical judgment.

The architecture relies on systemd for much of the system's functionality. Updates are per-image and atomic, and KDE Linux keeps multiple copies in case changes need to be undone.. Only Wayland session support is available, which aligns modern Linux desktop components (PipeWire, Flatpak portals, etc.) to create a coherent whole.

Beyond the end-user experience, there is an explicit goal for those developing KDE: Shorten cycles, reduce the cost of building dependencies, and make testing more deterministic.Compiling on top of the base with systemd extensions or reverting to any of the latest saved images simplifies the "break and fix" process of development. It promises greater speed (only building what you touch), greater security (easy rollbacks), and lower disk usage compared to environments where everything is compiled from scratch.

Ultimately, KDE Linux aims to be usable by everyone, from developers to users and hardware vendors, while keeping in mind that it won't be the most fine-tuned platform for ultra-specific uses. It does not compete to discourage other distros with KDE, but to raise the minimum quality of those oriented to Plasma, creating a clear and reproducible technical pattern.

KDE Neon, GNOME OS, and the "Reference System" Debate

The parallel with KDE Neon is almost self-evident. Neon's developers have never wanted to label it as a distribution: They define it as a repository based on Ubuntu LTS with live images. to test and have the latest versions of Plasma and KDE apps on a stable base. However, in practice, many people use it as just another distro, which has fueled debates and comparisons since its release.

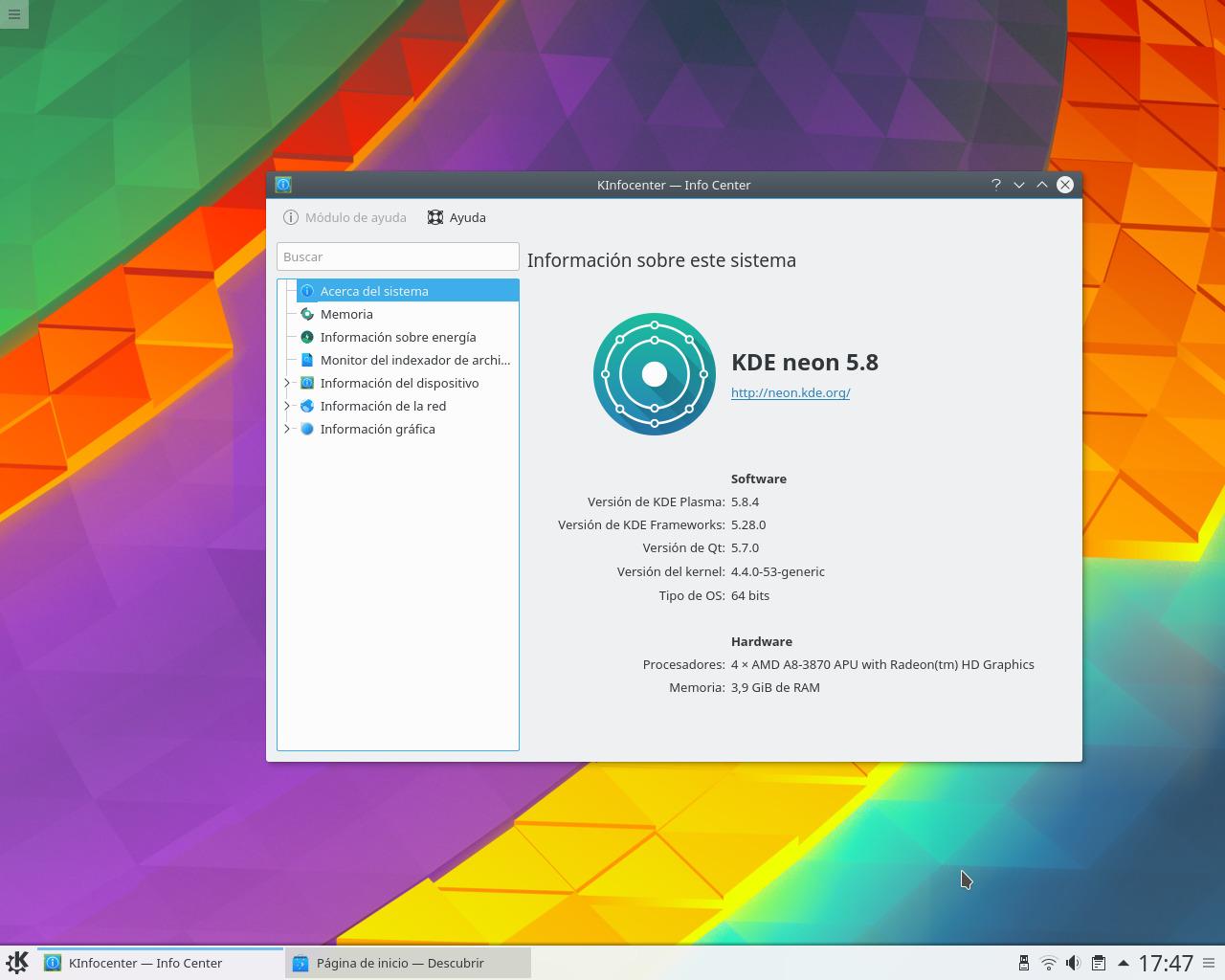

A veteran analysis of Neon, when it was running Ubuntu 16.04 Xenial, serves to illustrate the pros and cons of this approach. At that time, after installation, the environment was very minimalist: just a dozen applications like Firefox, VLC, Discover, Gwenview, KWrite, Ark, Dolphin (the file manager), Konsole, System Preferences, System Monitor and KInfoCenter, with Qapt as an alternative for installing .deb packages. This reduced RAM usage to around 400 MB when Plasma was first launched, disproving the "KDE heavy" stereotype.

But there were also hiccups: long times searching for partitions during installation, a slow first boot from GRUB to Plymouth, some crashes when installing proprietary NVIDIA drivers or when testing the camera with VLC, and the hassle with Discover when trying to get HPLIP for HP printers (I had to use Synaptic or the console). Even the appearance of GTK applications with Breeze was visually disturbing, and some areas remained untranslated.

In synthetic performance, with typical Phoronix tests of that era, the set failed to outperform Ubuntu Trusty in three out of four tests, although in daily use it felt snappy. The experience made the trade-off clear: the latest versions of Plasma and apps, a familiar and stable base, but some friction in drivers and settings, typical of a layer that prioritized innovation in the KDE stack over overall polish.

In essence, KDE Linux proposes something else: an immutable base, updates per image, and a build chain that aspires to reproducibility. That is, it offers a technical and experience reference, rather than just a fast track of KDE packages on Ubuntu.These are distinct missions that can coexist: Neon as a fast track for Ubuntu users who want the latest from KDE, and KDE Linux as an example of how a Plasma-centric system should be assembled from the ground up.

In parallel, the GNOME project is pushing its own vision with GNOME OS, which has evolved from a platform for testing new features in the environment to aspiring to a general-purpose offering. It shares with KDE Linux immutability as a model, Wayland and PipeWire as key technologies and the determined use of Flatpak for applicationsWhere it differs today is in the foundation: it's not based on a well-known distro but on carbonOS, by Adrian Vovk himself, now redirected towards this goal.

In GNOME OS, decisions such as the type of cycle (rolling, LTS, or hybrid) are still on the table. However, the integration of components such as systemd-homed and systemd-sysupdate, developed by Vovk himself, is clear. The awkward question is the same one that hangs over KDE: if Fedora exists (or KDE Neon exists), is there a need for an "official" desktop system? The practical answer is that both projects seek to establish a canonical technical reference for their stack, without prohibiting or competing head-to-head with those who already do it very well today.

Returning to Neon, that classic review ended with a mixed verdict: for Ubuntu loyalists who want the latest Plasma, it was appealing; for those who value Chakra-like, openSUSE-like, or finely tuned Arch-like stability, It was not worth the change except for receiving news a few days earlier.Putting Neon into context helps us understand why KDE Linux, if it comes to fruition, won't be treading on the same ground and could coexist as complementary references.

KDE Ecosystem: Technologies, Plasma-based distros, and project overview

KDE is built on a single principle: customization. Virtually everything is customizable, from KWin as the window manager to the visual styles of widgets and menus. The intention is that novice users find easy access to the most common options and advanced users can manually adjust the environment to their liking., without sacrificing usability.

The project, started in 1996 by Matthias Ettrich, has gone through key stages. Version 1.0 arrived in 1998 with a panel, desktop, Kfm, and a good set of utilities. Shortly after, Qt's licensing evolved to align with the GPL and, since version 4.5, with the LGPL, clearing up doubts in the free software world. With KDE 2 (2000) came DCOP, KIO, KParts and KHTML, the foundations of a modular, pluggable desktop with its own HTML engine. which, in fact, inspired technologies like WebKit at Apple.

KDE 3 refined the series with a few API changes and visual improvements like Keramik and Crystal icons (later Crystal SVG), establishing a streamlined release cycle. KDE 4 saw the return of the Plasma-based desktop and new frameworks like Phonon (multimedia), Solid (devices), and Decibel (communications), along with Strigi search and the NEPOMUK semantic desktop. The subsequent reorganization separated the KDE brand for the community and consolidated three pillars: Plasma, Applications and Frameworks.

Since 2014, Plasma 5 embraced QML and OpenGL to modernize the interface and improve performance/power, with the Breeze theme as its hallmark. In 2024, Plasma 6 marked the big leap to Qt 6, with 6.0 focusing on porting without losing features. 6.1 maturing the package with several intermediate updates and 6.2 moving forward with another round of polishing, before making way for new features in future releases. The cadence is rapid, and barring major changes, the API remains stable to make it easier for apps to work from one major minor release to the next.

On the foundation side, KDE Frameworks bundles over 80 libraries on top of Qt: KIO for transparent I/O to local files, networks, or virtual protocols; KParts for component embedding; KJS for JavaScript; Sonnet for fixes; Solid for hardware; ThreadWeaver for efficient parallelism; and more. Plasma offers workspaces for PC and mobile, and KDE Applications (KDE Gear) brings together nearly 200 apps integrated with the desktop., from text or image editors to office automation, video, music or web browsing.

Some emblematic components deserve mention: KWin as a compositor and window manager, Qt as a library for the graphical user interface, Phonon for multimedia, Akonadi for PIM, Kiosk for blocking functions in controlled environments and WebKit, which, although external, coexisted in stages with KHTML. Much of this fabric was integrated into Plasma with native effects comparable to those of Compiz at the time.

In terms of releases, the project is known for sticking to schedules, with rare and justified delays (such as 3.1 for security reasons). Major branches share binary and source code compatibility, which minimizes recompiles except for significant jumps. After each major release, the stable branch is maintained while the main branch cooks up the next iteration., with the minor ones focused on incremental fixes and improvements.

The KDE community operates without centralized leadership: decisions are made on mailing lists by the core developers, and legal and financial representation rests with KDE eV. The collaboration is broad, with hundreds of volunteers in coding, translation and art., and open channels for reporting bugs and requesting features in the Bug Tracking System.

Over the years, there have been criticisms: Qt's old licensing situation (now resolved with GPL/LGPL) or the perception of similarities with Windows due to usability decisions. The reality is that the high level of customization and the effects of Plasma/KWin allow you to build very different experiences., and themes and styles have evolved in each era to suit users.

In external cooperation, there have been initiatives with Wikimedia to expose content via web services, and several KDE editors and players have integrated Wikipedia-connected features. That vocation to integrate and not live isolated from the rest of the desktop and the web explains the good fit with portals, Flatpak portals and the transition to Wayland.

When it comes to where to find pre-installed Plasma, the list is long and varied. KDE's own website lists popular options and recommends checking out each project's pages to decide. Among the best known are Fedora KDE, Kubuntu, openSUSE (Leap and Tumbleweed) and KDE neon, and there are many more prepared for specific tastes and needs.

In addition, there is a wide range of Linux and BSD distributions that offer KDE Plasma by default or with official variants. Some historical and current examples include ArtistX, Aurox, BackTrack (with KDE 3.5), Chakra, Debian GNU/Linux (KDE variant), DesktopBSD, Edubuntu KDE, Fedora-KDE, Freespire and KaOS, among many others featured in community listings.

The payroll continues with Kanotix, KDE neon, Kubuntu, Kurumin, Linspire, Mandriva, Manjaro, MEPIS, openSUSE, Pardus, PC-BSD, PCLinuxOS, Q4OS and Sabayon Linux, each with its own combination of base, update pace, and packaging philosophy.

They complete the panorama Aptosid (formerly Sidux, on Debian Unstable), SLAX, SUSE Linux, VectorLinux, and XandrosThe bottom line is that the Plasma experience can be enjoyed at virtually any pace and system model: stable, rolling, hybrid, immutable, with classic packages, or focused on universal containers and formats.

One last useful note for anyone considering making the jump to KDE Linux when it matures: The spirit is not to compete with these distros, but to serve as a reference. on how to build a modern, secure, reproducible KDE desktop with a technical foundation that others can adopt or adapt. Those who prefer Kubuntu, Fedora, openSUSE, or Manjaro will still have excellent and well-maintained paths.

Looking at the big picture, KDE Linux paints an ambitious yet pragmatic picture: an immutable system with atomic updates, Wayland by default, apps in Flatpak/Snap, and clear paths for specialized software; clear rules for NVIDIA across generations; and an experience designed for both end users and developers who require speed and determinism. If you add to that the maturity of the KDE ecosystem, its history of constant evolution and the variety of distros with PlasmaThe remaining image is of a desktop that not only adapts to each profile, but also aims to lead how a modern system should be built around it.